High costs are killing US transit projects.

The high price of transit in the US is killing and cutting back critical projects, and its impact is going to go much further if it is not addressed.

As is well-covered in the Transit Costs Project, the amount of money needed to pay for transit projects in the United States and the Anglosphere in general is eye watering. Projects costing more than 5 times as much as they do in other countries, or even more upsetting: 5 times as much as they did a few decades prior (general inflation is nowhere near that). I think a lot of the time when technical advocates mention costs, the general advocacy community does take interest but perhaps sees it as more of an unfortunate feature of projects, rather than a crisis — But I truly believe it is the latter.

I have discussed costs in a lot of detail in the past, but now is a good time to reflect because in the past month or so, several high profile projects have been cancelled or seriously cut back because of high or rising costs.

These include the Project Connect Transit Program in Austin, Texas, the second downtown tunnel as part of Seattle’s ST3,

the LaGuardia Airtrain,

and the King of Prussia Extension in Philadelphia.

Of course, I’ve already heard folks saying that some or most of this is not about the costs of projects, but I think it’s completely foolish to suggests costs didn’t have a role.

Coverage of both the LGA AirTrain and KOP rail has both been closely focused on their ballooning costs, and in the case of the King of Prussia project, an inability for SEPTA (the transit agency running the project) to handle the costs was given as a reason that the FTA wouldn’t fund it — and that makes sense. The state of much of Philadelphia’s existing rail infrastructure ranges from poor to very poor, and thus spending money on an extremely expensive suburban rail extension to the Norristown High Speed line feels like a weird inversion of priorities.

Of course, the project also had its critics because it was not exactly a slam dunk — at least by US standards, mostly serving what are not currently transit-friendly suburban environments with a lot of complex engineering required. But, this Twitter thread captures my feelings about so many such projects very well.

While we can argue about planning decisions, a lot of the projects that we’ve seen cancelled or doomed to purgatory would be a net benefit to their respective cities and transit networks. A lot of projects would be good if you didn’t have to pay much for them! In this way, costs and their impact on projects are a sliding thing. A great project becomes painfully hard to fund, and an okay project is just expensive enough that it’s not worth it — even if an okay project today could spur the type of land use and transit ridership changes in the future that might make it end up being a good project down the road.

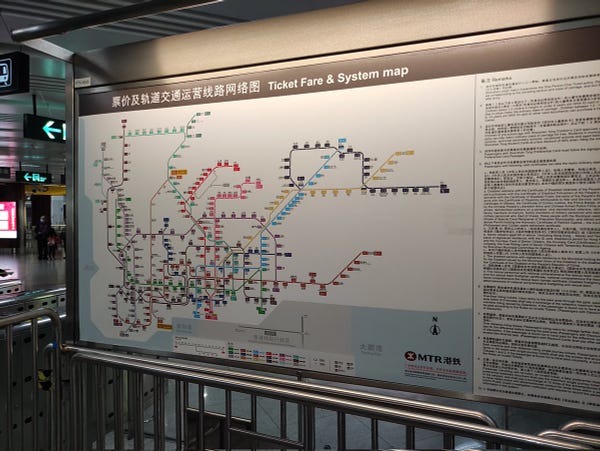

As luck would have it, the litany of projects blowing their initial budgets came at the same time as a friend was visiting Shenzhen, China, which has a big metro network that has grown a lot in the last ten years.

What I found interesting, or perhaps unsurprising, was the usual comments on the size of the network, which are:

“If only [the US] funded transit we might have a network like this!”

“The US spends so much on highways, if we just spent it on transit we could be like China!”

These two notions are really problematic.

For one, the US does fund capital expansion for transit projects. While it could stand to better fund operations — operations are also particularly inefficient in the country, many systems have multiple staff members on every train, and few lines are automated — even in cities with extremely high labor costs. China by comparison builds significantly more automated metro than the US despite much lower labor costs — the US is building very little metro at all.

At the same time, the transit funding programs seen in the LA and New York regions (just to pick two) are incredible: In most low-cost parts of the world ,they could build several entire metro and regional rail systems. The issue is not that the dollars are not being spent, just that they aren’t being used efficiently. Spending more could quite possibly only make these problems worse, and so in some sense, the fact that hard decisions about projects need to be made is good: It will make people think more about costs, and highlight that these projects do have a ceiling.

I’ve said before that I think resisting extra spending runs counter to temptation. It’s easy to say “Fund Transit!” but much less satisfying to try and push for the complex reforms needed to make building it more efficient. It’s not easy, it’s hard — and thats a big part of why I find this quasi-dismissal of the state capacity of a place like China irritating.

The other very frustrating notion is the idea that since the US spends a lot on highways, it should do the same on transit, or that it’s at least acceptable. Unfortunately, I think this is wrong.

Highways, just like transit and a lot of other infrastructure in the US, cost far more than they should, but the sense I get is that the US is probably spending more money on new transit now than new highways (at least urban ones). So even though we don’t like highways — the fact that they cost a lot doesn’t matter much (and it shouldn’t) because it will limit new construction, just as high costs do for transit (though yes perhaps less if highways are seen more favourably). The thing is, even if lots of new highways are not built, that doesn’t really matter as the US already have tons. Basically, everything infrastructure costs more in the US, but high costs for something we want like transit is a much bigger project than with already plentiful (and wildly overbuilt) highways.

So, we really do need to talk about costs, and debunk some of these very unhelpful statements that keep the important questions that need to be asked from being. From what I can tell one of the biggest reasons projects cost so much in the US, is that few seem to really care that they cost so much, and so few — if any — decisions from project inception are made through the lens of creating a project that is affordable. Talking about these issues is probably a good way to change that.

And I think it’s important to consider a positive future with low costs, and to create a positive vision of what we should be working towards. What does such a future look like? Well for one, instead of projects within a city having to battle it out for funding, we could just build all of the reasonable projects. And agencies like the FTA would have less influence because many projects would be inexpensive enough to fund locally. This would of course speed things up and allow even more to be built.

Low costs would mean that cities like Philly could be majorly overhauling their existing networks while executing a number of major capital projects at once — just as we see with Toronto today. Cities like New York could be working on several new subway extensions, new lines, multiple rail links direct to each area airport, and possibly start replacing heavily-used bus routes with light rail, as well as overhauling regional rail with new and upgrade stations, and through running frequent service — all while finishing the capital upgrade works originally pushed forward by Andy Byford — in short, it would be amazing.

And this amazing expansion would not just have an impact on transit — the positive externalities of low-cost transit building would have impacts that reach far and wide. Housing prices would come down as transit access became more equitable, and the additional mobility would allow for more efficient commutes, more access to opportunity, and a more prosperous society. The demand for private cars would also fall — and thus initiatives further limiting them such as congestion pricing and additional bike and pedestrian infrastructure could be accelerated. All of this would come with a lot of soft power — the US could perhaps be seen as a real player in the game of creating cities for people. And that’s something worth fighting for.

1. The Transit Cost Project report is excellent. The advice re too much being spent on consultants and inadequate in-house managers rings true in NYC.

2. Because KOP buildings are spread out, a bus loop to rail would work best. The latest KOP rail; proposal merely linked to the Norristown High Speed Line, which I love for a fan-trip, but only goes to 69th Street, not Center City.

3. As Reece suggests, the pot of money is only so big. There should be morte pressure to spend it effectively & efficiently.

Practical Engineering did a great video about why construction projects always go over project and the problem is if you underestimate the cost an infrastructure project, the project will likely go over the initial budget, the public and governments become annoyed but if you overestimate the initial budget, the project is very unlikely to gain approval to go ahead.