The Eglinton Crosstown is delayed again. What's wrong with this project?

What has gone wrong, our unrealistic expectations, and how to fix this mess.

During a bit of a recent media craze, we’ve heard that Toronto’s Line 5 — the Eglinton Crosstown — will not be opening in 2023 and has a ton of construction quality issues that are holding up commissioning and ultimately the line opening.

As with a lot of transit issues, at least some of the problems have been visible to careful observers, which means few people in the transit discourse are really surprised that there are problems with the Crosstown that will further delay its opening. But I think stepping back, it’s worthwhile to take a bit of a macro look at the problems to see if there are things we can do better in the future.

This article is a really deep dive, so if you enjoy it please make sure you’re subscribed (it’s free), share the article and that you leave a comment about what project you’d like me to do an in depth article on next!

To start, the Crosstown is super delayed (though not Berlin Brandenburg airport level delayed - ~10 years) — The project was meant to be done in 2020, and it still likely won’t be open until well into 2024. It’s completely reasonable for some major infrastructure projects to be delayed by COVID-19, but what’s interesting is that if the Crosstown had actually run on schedule, COVID would barely have impacted it because construction would have mostly wrapped, and trains would have been testing when the world went into lockdown.

But there’s a more important issue here. Everyone knows big projects are usually delayed, so that really should not be surprising us at this point, especially because the best comparables — other rail rapid transit projects in Ontario and Canada — have been running really late. That’s not an excuse of course, but we need to step back and look at our recent record.

Evergreen Line SkyTrain Extension - 6-month Delay, Opened 2016

Toronto York Subway Extension, 2-year Delay, Opened 2017

O-Train Line 1, 1-year Delay (and clearly rushed and poorly executed), Opened 2019

Edmonton Valley Line, Projected Opening 2020, Delayed 3 years

What’s key to note is that the Eglinton Crosstown is more complex than any of these projects, all of which ran substantially delayed. The York Subway Extension (Toronto Subway) and the Edmonton Valley Line (modern high-capacity tram) are probably the closest comparables, and the York Subway had no complex interchange stations, while the Valley Line is just a tram with a few elevated sections, a short tunnel, and a big bridge. Meanwhile the Crosstown has more tunnel, several interfaces with at grade GO corridors, a connection to Line 2 of the subway at Kennedy Station, and two interchanges where it crosses just under Line 1 of the subway (these have generated a lot of delay).

The big point here is that recent projects simpler than the Crosstown were delayed similar amounts! So we shouldn’t really be surprised that the Crosstown is facing similar problems.

Of course, you might expect that such problematic project delivery would lead to changes that would fix these problems, but big infrastructure projects are multidimensional — you can easily change some policy or input that has little to no impact on outcomes (or makes them worse!). At the same time, it’s worth asking if we as a society have really had a discussion about what needs to change so that big public works project start, well, working again.

Now, if you’re familiar with the infrastructure construction space, you’re probably aware that it’s very common to lowball budgets and timelines to try to win political approval and the like, and that’s surely a problem here. The lowballing of timelines doesn’t mean that timelines couldn’t be faster, but they don’t get faster by pretending the things you want to do will happen unrealistically quickly — you need new and better processes.

Of course, part of the problem here is clearly media pressure. You will never get as much attention for finishing early and under budget as late and over budget, and this means that contingency that amounts to slack is often added to projects post lowballing to avoid letting people down. If you increase the budget enough, and give yourself enough time, you can never be late or over budget! Of course, like the lowballing I just mentioned, this slack doesn’t actually protect the project — it creates an unhealthy sense of comfort with moving slowly early on, even though you really need to be running ahead of schedule to protect from unforeseen problems.

The bigger problem with both the points I raised above is that these schedule and budget estimates are fundamentally disconnected from the projects: they aren’t part of the initial planning but rather an 11th-hour addition that does not change the fundamentals. A poorly planned project is just going to take longer and have a higher risk of delay — adding contingency will not save you. I keep bringing up budget because it is not disconnected from timelines: delays increase costs because you have to pay out more hours to workers and project staff, and you also increase your risks. There’s a fantastic recent book on just this topic here.

But, while Toronto is having all of these problems, another city across the country is in a very different position. When you compare Vancouver’s recent transit projects to those happening in Ontario, the results are rather shocking. The Canada Line built for the 2010 Olympic games was completed on budget — which was a fraction of the price of current projects — and ahead of schedule. And even the Evergreen Line referenced above was only delayed about 6 months, despite having major subsidence issues resulting in large sinkholes when boring the project’s tunnel. Clearly, something is going on in BC (more likely multiple somethings) that is leading to better projects, and more and more I am urging people in the rest of Canada and the world to pay attention and be curious about those things. This is a great case study in how to build and plan better projects.

The obvious question that gets asked here is “How did they do it in Vancouver?” The easy and oft repeated answer is that the project was completed on time because it was a key component in the aforementioned 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympic games, but that’s beside the point. Winter games are not an engineering and planning solution to get subways built fast and on time; instead, the pressure of an event ensured a critical project would be completed on time — by using smart construction methods, experienced contractors and extremely careful management. Lower risk approaches were taken, which reduced the risk of the project being delayed, and this also reduced the risk of cost overruns — which are often a direct result of delays!

So what were some of these techniques which were implemented?

One of the obvious ones is cut-and-cover tunneling. the Canada Line project more or less used cut and cover where it was easily practical — notably on the wide Cambie Street on the southern part of the tunneled section in the city of Vancouver. Cut-and-cover works were completed fairly quickly (remember, the whole project was three years), but even still, public and media backlash has meant that it will likely not be used again anytime soon. Shop owners sued successfully for disruption and the media has poured gasoline on the fire for years, but it seems pretty clear to me the disruption on Eglinton Avenue — where works have been going on for several times as long — has been far worse.

If citizens and businesses are going to scream if you do the construction method which is faster and less expensive, and probably just better for society as a whole, making it no longer politically acceptable, that’s a really bad outcome! There is almost no discourse where people are being asked whether they really think a method of construction that will take way longer, cost more, and be almost as disruptive is really better — but, there should be.

Stations are one of the most costly and time consuming parts of building a transit line, given their scale and complexity, and so the Canada Line massively simplified these facilities as well — while providing the same capacity as the Crosstown. So what does this look like?

Well, the Crosstown stations are deeper, with multiple intermediate levels, multiple entrances, bus terminals, and are also much larger. The platforms on Crosstown stations are more than twice as long as those on the Canada line at 90 meters (Canada Line stations are 40 meters with knockout panels to extend to 50 meters).

Now, I get asked endlessly — how can the capacity of the stations be the same if the trains themselves are so much longer on Eglinton? And the answer is simple — train length != system capacity. The capacity of a rapid transit system primarily depends on train length, width, layout, and frequency, and while Eglinton’s trains are longer than those on the Canada Line, the Canada Line trains — which are traditional subway trains rather than trams — exceed those on Eglinton in each other category. They are wider, have a more open layout, and more doors allowing for more frequency.

The stations being roughly 2x the size on Eglinton alone massively increases the cost of the project. You can learn more about this from the Transit Costs Project, who discusses the impact of design decisions like this in great length. The Canada Line appears to have started from the trains to determine the minimum acceptable size for all other infrastructure, so each Canada Line station has only a couple fare gates and one entrance. Essentially, while Eglinton has nice large stations, they are typically larger and more intricate than they need to be for the number of passengers who will conceivably use the system; the multiple entrances and other flourishes are nice, but they are nonessential and other systems do fine without them. As with the Canada Line, additional facilities like additional entrances can always be added later (especially with simple cut-and-cover stations) when travel patterns actually materialize showing they are needed, and this gives you the benefit of being able to be wrong about where the demand really is.

The fundamentals here are that you make different decisions when cost and speed of construction are a priority. It’s better to build transit which uses frequency to its advantage to increase capacity, can use smaller trains and stations, and since passengers will arrive in frequent but small bursts, the actual flow of passengers into and out of the station will be less “spiky”, reducing the need to size things for infrequent rushes of passengers coming off a big train. It’s essentially a tradeoff between more sophisticated operations (enabled by automated trains) and more complex capital construction.

Of course, while it may be suboptimal to build a high-capacity subway for use with trams, just because the design isn’t ideal doesn’t mean it should take longer and cost more to build — so what’s the issue with that?

I think a lot of the problems here come down to project structure, timeline, and design. The Crosstown started its existence as a TTC project, but was eventually “adopted” by Metrolinx and run as a P3 process — which has gotten it a lot of bad press.

But the Canada Line was also a P3, so what was different? Well, for one, the Canada Line was a very open project. The government have a rough specification for what it wanted — 25-minute travel time from Downtown to the Airport, a certain capacity etc. — and let the bidders go at it. One successful bidder would build the system, buy the trains, and operate it for 30 years.

By comparison Eglinton was much more constrained and complex. Tunnels were a separate contract done before the stations and maintenance contracts (meaning using cut and cover to build cheaper shallower stations wasn’t in the cards), and trains were chosen beforehand and purchased separately by Metrolinx (meaning using smaller trains to build cheaper smaller stations wasn’t in the cards). The project is also going to be operated by TTC, rather than the projects builders — which will probably create conflict if maintenance done by a third party is not up to the agency’s spec. The project has been broken up into tons of small parts that creates complexity and many interfaces and parties who are involved. And I haven’t even mentioned the legal action that occurred when Bombardier could not deliver the trains for the project on time! And the project itself was conceived by a different group of people than those who had to implement it (The City of Toronto → Metrolinx)!

The period of time the project has taken to construct and plan is also frequently blasted in the media, and on social media — but, as I just mentioned the timeline was clearly not optimized for quick completion. While works on the Canada Line happened in parallel with the longest portions - station construction, starting immediately. By comparison with the Crosstown, tunneling work was mostly complete before station building even started, stations were actually only starting to be seriously worked on in 2015, years after TBM’s were first in the ground.

Despite all of this, and my fears that slower, more expensive projects in Ontario are influencing those in BC in a negative way, the better subway building of Vancouver is living on for now.

The Broadway Subway is not a perfect project, but I find it fascinating to compare it to the Crosstown — both Eglinton and Broadway are dense urban streets with lots of traffic, and both subway projects need to intersect an existing subway line. That being said, despite having years of inflation and potentially negative influence on it, the Broadway Subway still seems to be better designed than Eglinton, and this is reflected in its timeline — which is only about 5 years from start of tunneling to line opening.

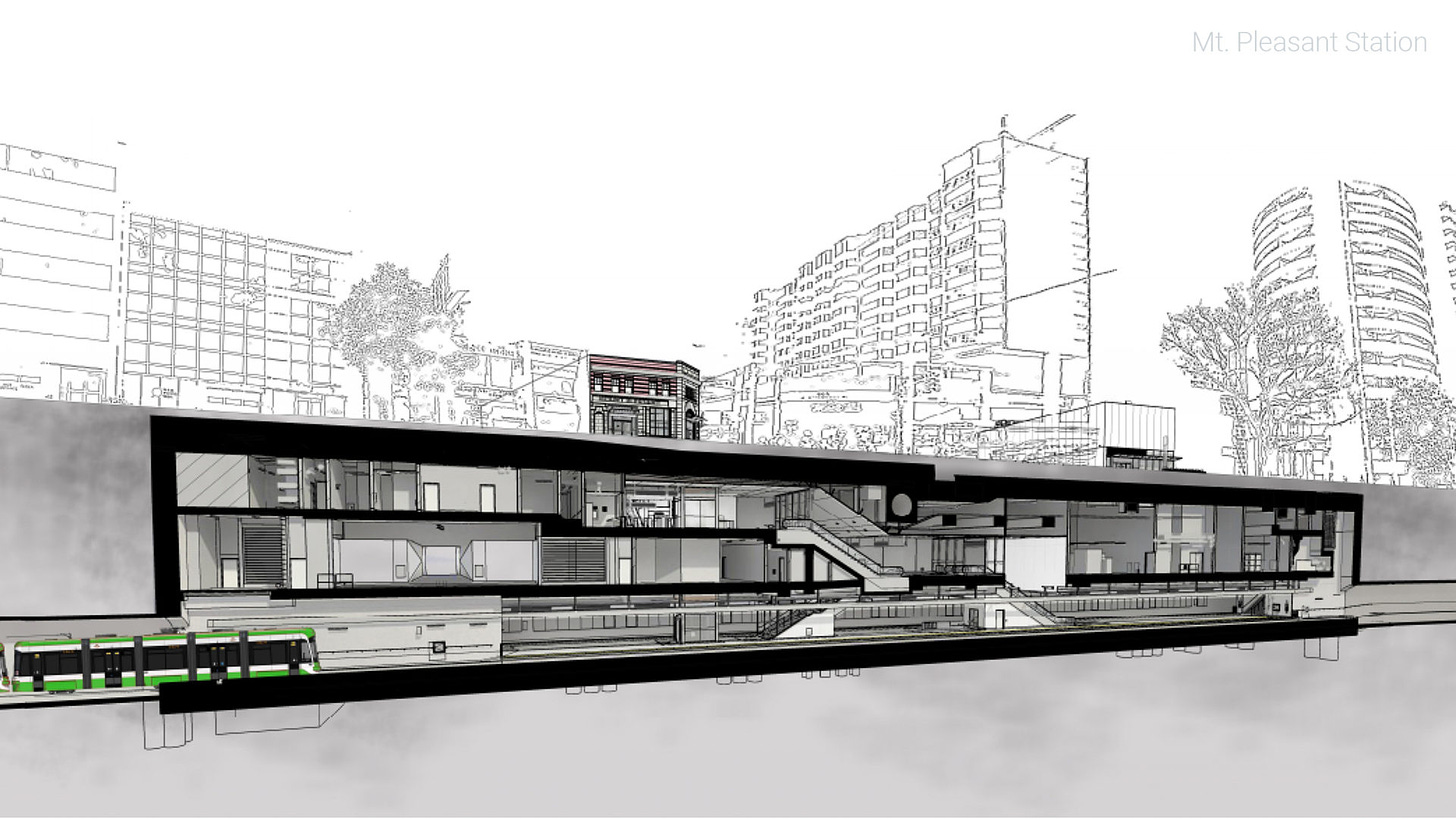

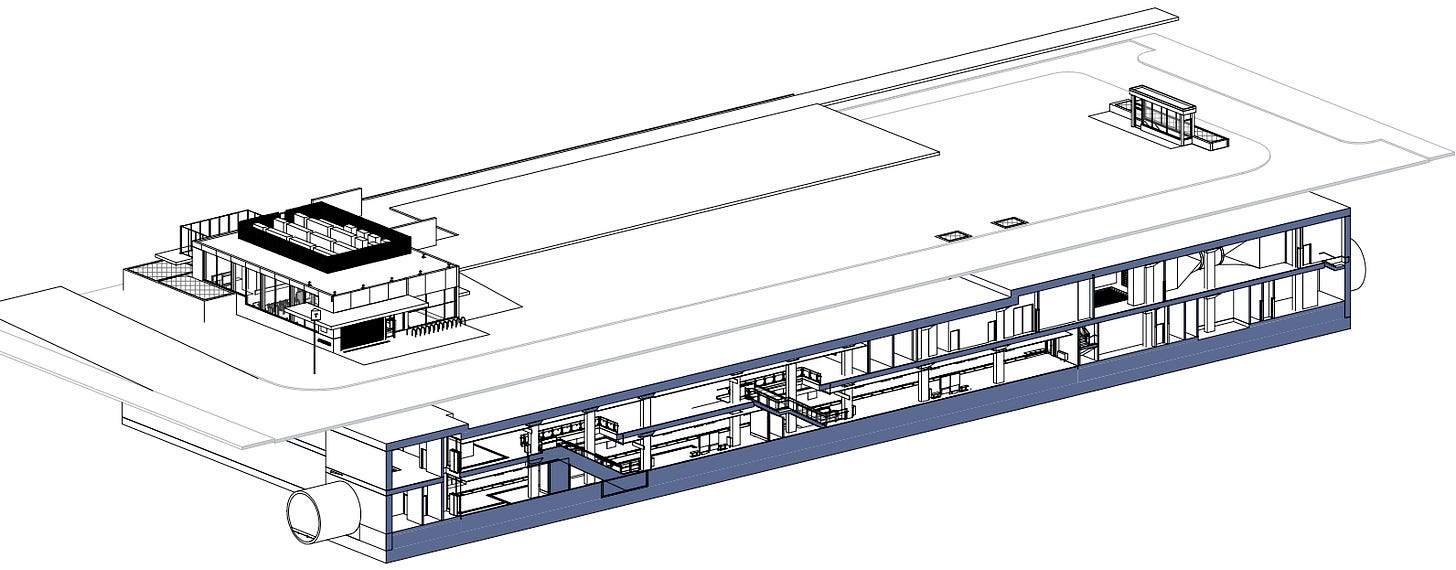

For one, the phasing of the Broadway Subway seems more logical: Station boxes will be excavated prior to tunneling (on the Eglinton project station headwalls were the extent of pre-tunneling station construction) — which is still being done with TBMs, which means final station construction can begin the second the TBM passes through each site. This more efficient phasing alone will shave years off the project. The stations on Broadway are also all being built cut-and-cover under decks, while several on Eglinton used the costly and risky mining method. Even just comparing the station designs, Broadway’s, despite being built for 60% more capacity (SkyTrain Millennium Line is designed for 25,000 ppdph, while Eglinton is designed for 15,000 ppdph) are much simpler. See Mt. Pleasant Station on the Crosstown Below.

And then Mt. Pleasant Station on the Broadway Subway (funny that both have a station with the same name I know!)

Notice how the Vancouver station has one entrance and a small emergency exit, while the Toronto station has two large entrances. The Vancouver station is also a little bit shorter in length. Probably most interesting to me is how the station in Vancouver manages to remove a whole vertical level from the design. Passengers descend from street level to a mezzanine and then down to platforms, meanwhile in Toronto there is an additional sub-mezzanine level! There also appears to be way more back of house space in the Toronto station design, and this is all for a station which is designed to move less people.

And it’s not just on the west coast where there are lessons to be learned. Montreal’s REM project is building a 67km regional metro network faster and less expensively than the Crosstown, and while much of the trackage on the REM is at-grade or elevated, it does feature new tunnels, much higher capacity, multiple maintenance facilities and a number of other major technical challenges that Eglinton does not. Despite all of this, the REM costs less than Eglinton and was only even announced in 2016 — with its first phase being set to open in the next few months. That’s a substantially more efficient project — given major construction on stations on Eglinton started, and tunnels were completed before the REM had even been announced. Perhaps even more fascinating is that despite the low cost of the REM, the Blue line extension being planned by the STM — Montreal’s Metro operator — is set to break price records as one of the most expensive projects ever done in Canada on a per kilometre basis. This is despite the fact that the line is rather peripheral, not unlike Eglinton!

So with all of this out of the way, what do I think the key takeaways should be?

Understand the context in which projects are being built — delay is common, but so are long timelines! We are facing an Ontario-wide, if not Canada-wide problem.

Realize the real tradeoffs that are made to avoid bad press, seek political approval, and avoid litigation — even if they ultimately make projects harder to build and more expensive.

Note that the projects being built in Canada are usually in the right places and will likely have high ridership. They are fundamentally the right projects (albeit with design tweaks) — it’s execution that is the issue. Alon Levy has a great article on this topic.

If we are the first to do something — think Ottawa’s complex busway → rail conversion, or Eglinton’s high capacity tram subway — maybe consider whether there’s a reason other jurisdictions where transit is more developed and better understood didn’t do the same thing!

The media has a role to play in these dynamics. Toronto’s “BlogTO” culture of chasing clicks and headlines by hyperbolizing problems and disruption dumbs down conversation about important issues and distracts from underlying problems — Crosstown construction has been winding down for years, but people keep talking about “disruption” because it’s just sort of a topic for pop conversation!

Curiosity is essential. Media, advocates, and politicians should not only be asking why projects in Toronto are going wrong, but how projects have gone so much better in Montreal and Vancouver. The arrogance and exceptionalism of thinking that Toronto must be best at this because it built the first subway in the country and has the biggest system is really bad.

Speaking of Transit Costs Project, what about an in-depth look at the Cambridge, ON LRT extension?