Los Angeles is a great city and one that is rapidly building more transit. From a subway extension (most of the way) to the sea, light rail (most of the way) to LAX, and much more on the way, few cities anywhere are improving their public transport systems as quickly.

The rapid buildout of LA’s rapid transit network is undoubtedly positive, and the city is going to be all the better for it — which I talked about in a video last week.

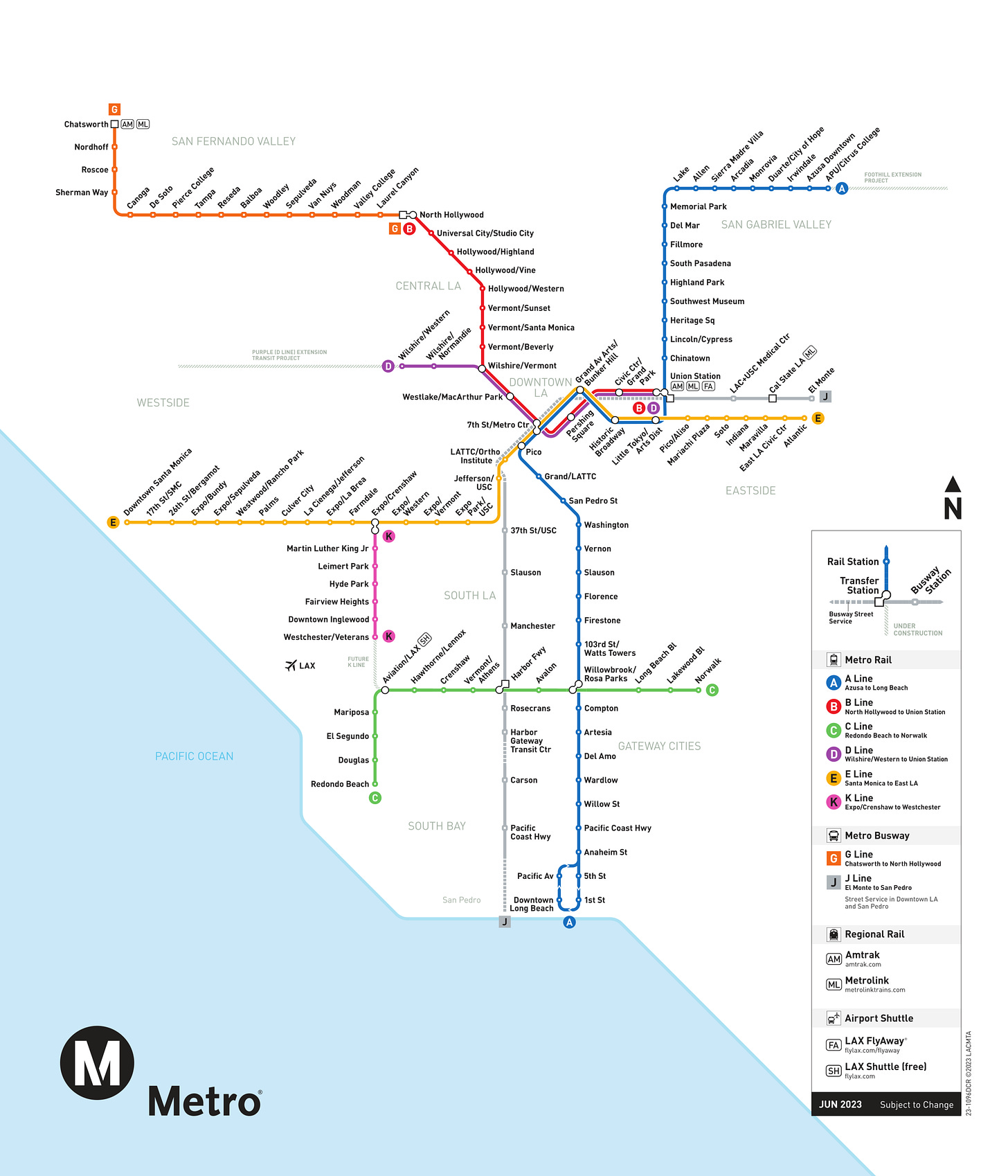

But there’s something missing from the network, and it can be hard to see just looking at metros rail map.

At the moment, Metro’s rail network is flat — in that it is a single network composed of a wide range of rail lines of different technologies, alignment styles, and travel speeds.

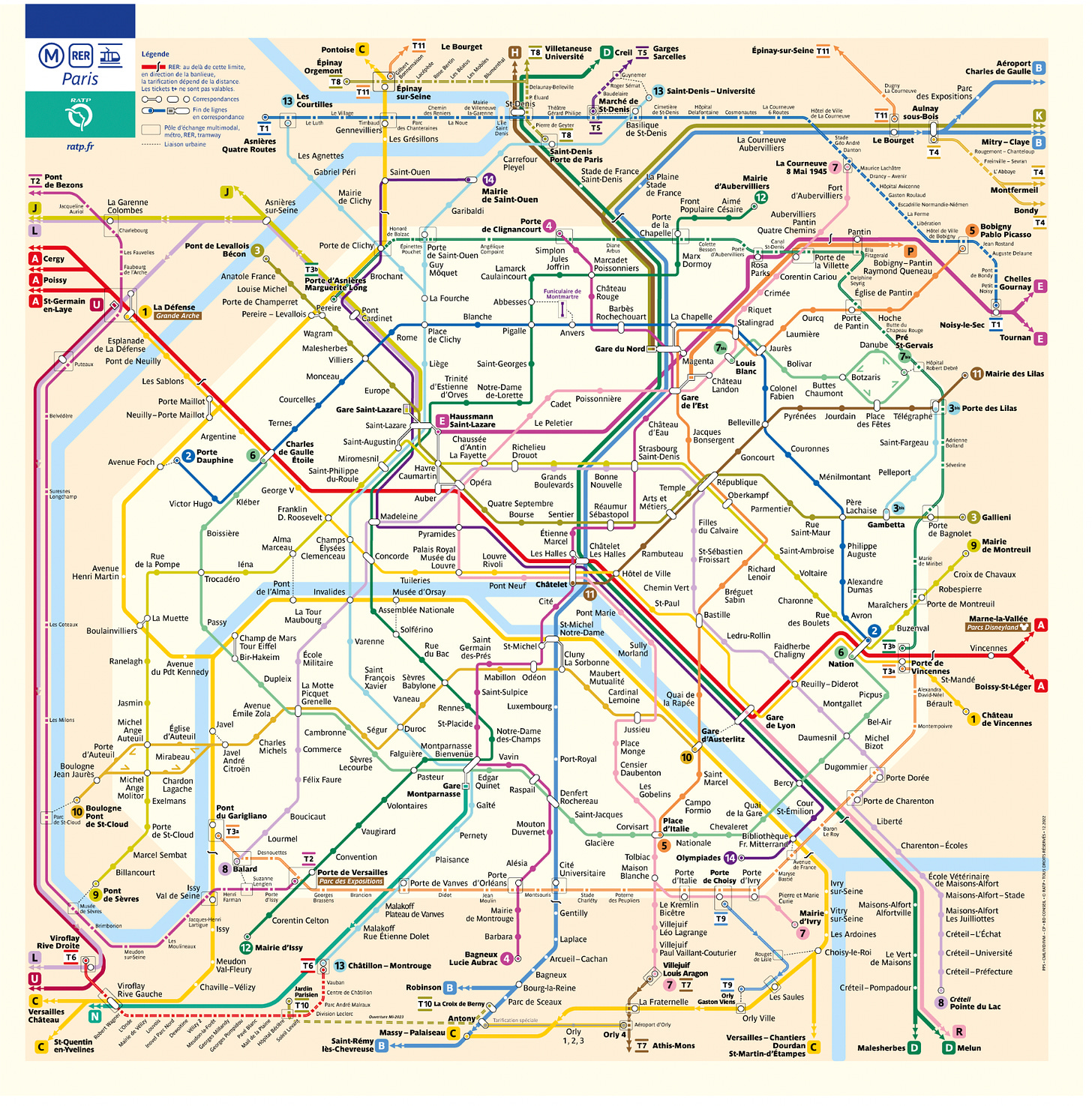

Contrast this with a city like Paris: In Paris, there are a number of independent layered public transport networks that connect the city as can be seen on a network map. It’s important to note that in Paris’ case, these networks are not even just layered and complimentary, but rather are increasingly independent. Major destinations like La Defense are already connected by each independent network, and the same is increasingly true of destinations like CDG Airport. That means that while these multiple-layered transit networks are complimentary, many journeys on the network can be completed without ever changing transit mode.

On the other hand, there is no such natural layering in Los Angeles. Metro currently is at a stage of its growth where the focus is providing any rail service to major destinations as well as along major transportation corridors. But, this is not inevitable by any stretch of the imagination.

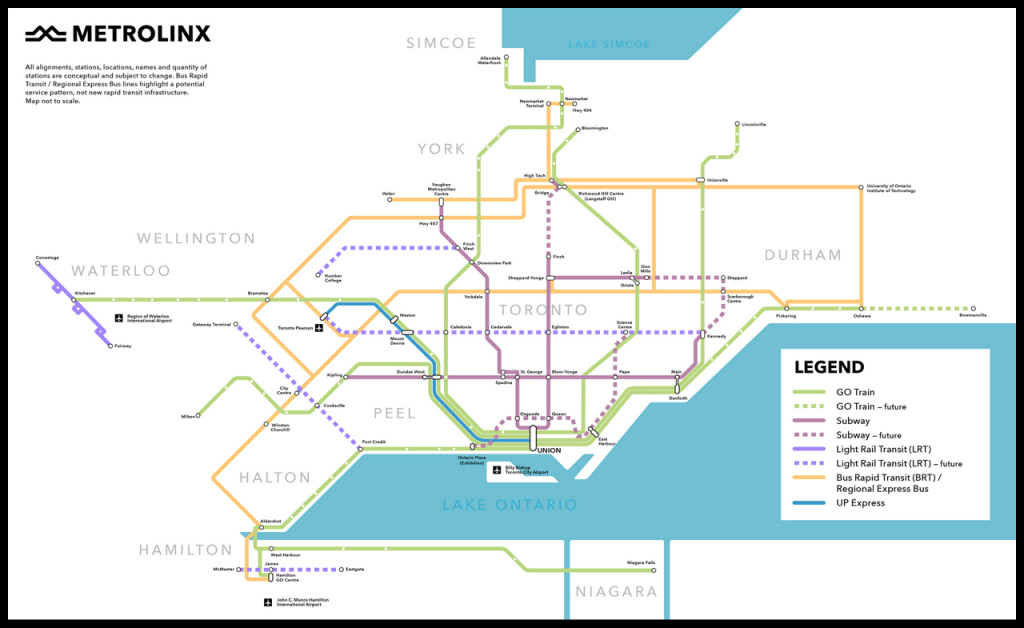

Even Toronto is to some extent creating multiple independent, layered, transit networks, with key locations like Toronto’s downtown core, Scarborough, and Toronto Pearson airport planned to receive service from both subway and regional rail. In some ways, the “U” of line 1 of the Toronto subway and the cross-city route of line 2 can be seen as local parallels to the broader “U” formed by the Stouffville, Kitchener, and Barrie lines, and the broader cross-regional route formed by GO’s Lakeshore line.

Now, while LA is not wrong to prioritize connecting most major destinations once before it gets to creating multiple connections, what it can and should do is think long-term about how the network might eventually look. That can help the region plan for where to put lines belonging to different networks.

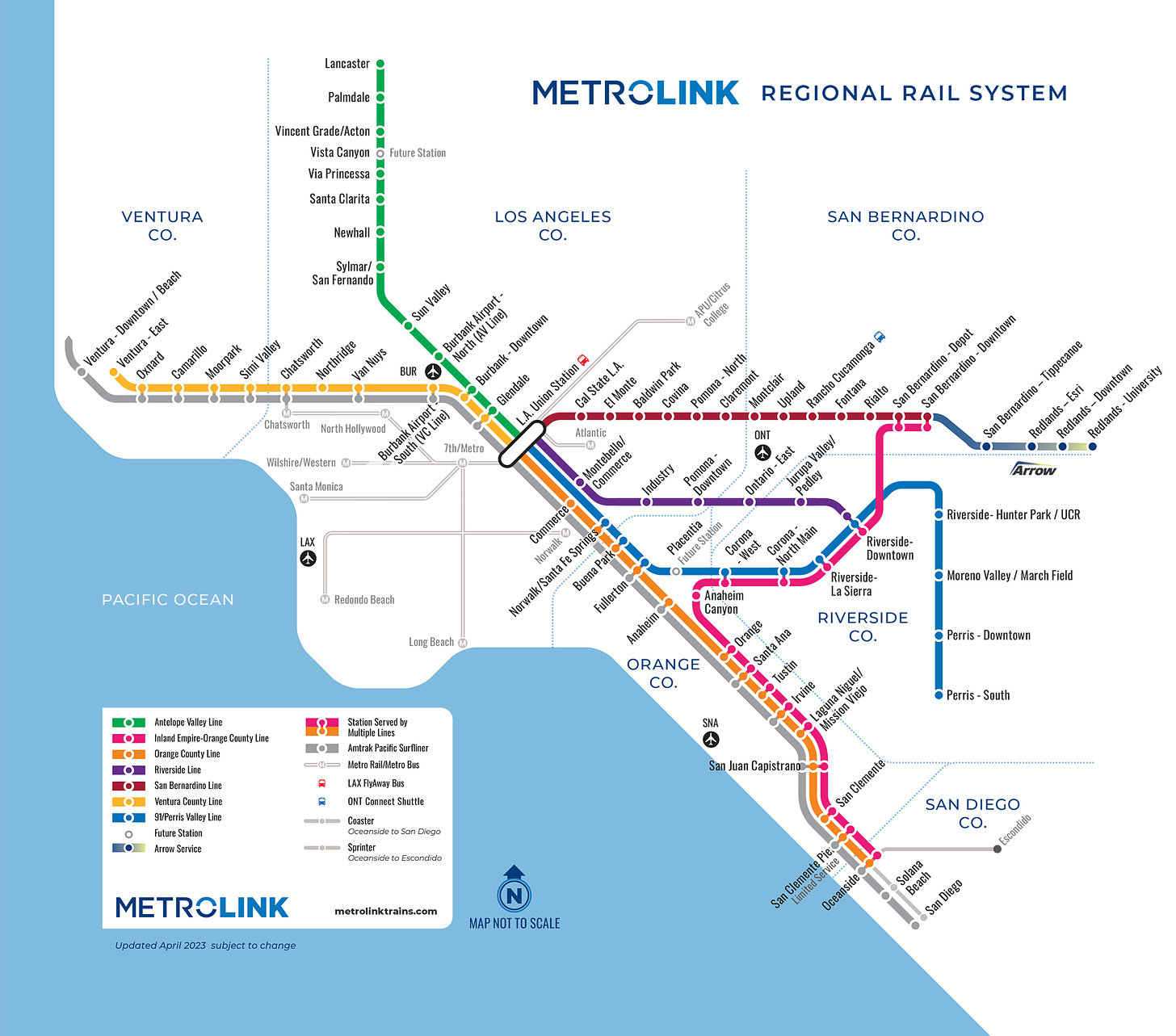

To some extent and in some places, that decision will probably be made based on what infrastructure already exists. For example Metro’s A line out into San Bernadino county can be augmented by Metrolink’s San Bernardino regional rail line, which it will connect back up to with the Foothills extension.

Why does it matter?

Having multiple independent networks like the ones seen in Paris and to some extent in Toronto seems like the obvious result of creating a bigger and denser public transit network, but it’s not necessarily obvious why that network should be made bigger and denser along the lines of multiple-layered networks.

For one, by providing a series of network layers, you can create layers that serve different trip types and numbers of people. The backbone layer is likely some form of regional rail which is the fastest, highest capacity, and also likely most expensive to build out. The high cost is acceptable because the high speeds and capacity provide massive value, and the capacity is necessary because the speed is attractive and will draw large numbers of passengers, but also as the “coarse” layer many trips will rely on trunk segments of the backbone network to get them from one general area to another. Connecting local lines and layers to the backbone — as LA will do with its Metro/Metrolink connections in San Bernardino county — is what helps the different layers interact as local and express journey options.

Capacity is also an important consideration. Having networks of the same mode across the city avoids having, say, a train line dump way too many passengers on a light rail line creating an overload. At the same time, it also allows the maximization of capacity on inherently lower-capacity transit modes. If cross-city journeys can be made on regional trains, then “local” metro trains can play the role of “distributor”, allowing each metro train to move many times its capacity by loading and unloading across the city — I’ll write a future article on this topic to discuss it in more detail, so make sure you’re subscribed so you don’t miss it.

Of course, capacity is also just higher when you have multiple parallel lines connecting various destinations. I’ve talked about it many times before, but much of LA’s current transit buildout leaves it in a trap: Many of the existing light rail services are much less fast and frequent than they could be, but if the lines started moving far more people because they were fast and frequent, light rail would likely not be able to cope with the demand, thus the need for more regional rail and subway lines. When you have layered but connected networks, you also get to benefit from network redundancy, not only are there often multiple routes between any two nodes in the network, but travellers are also more able to divert around problems — improving the real world capacity of the network and its reliability and plasticity under strain.

For a city like LA, and acknowledgement that it is eventually going to need these independent-layered networks, could let the city better plan for the future, laying the foundations for future projects now. The obvious places that need attention are the corridors south and west from LA Union Station, where there are light rail lines, but nothing higher-order. The extension of the D line subway will serve the “west-of-Union” regional corridor in the interim, but some form of regional rail is likely going to be needed along this route (or several subway lines); the same is true for the “south-of-Union” regional corridor to Long Beach. In the future, connecting these regional corridors with an arc (likely travelling via LAX) will likely be the role of the Sepulveda line’s southern extensions, but based on what I’m hearing about that project it likely won’t have the speed or capacity to serve that role into the distant future.

More is needed, layers are needed.

An advantage with layering is alternative transit routes. My daughter, who lives in Paris has a choice of two metro lines and the RER to get to work. Although one is more convenient and comfortable for her, she does not need a car for backup in case one line is out of service.

The line will carry ~27,000 pphpd after the platform extensions which is pretty decent. It's certainly not world-beating, but I think it's a pragmatic balance between need and means. Building a mainline rail-style service along the 405 would be amazing, but also incredibly difficult. There is a 10+ mile gap between the harbor sub and the VC line, and building brand-new rights-of-way is incredibly difficult in the US.