Vancouver (And the Pacific Northwest) should invest more in earthquake resilience.

Disaster preparedness should be a much bigger consideration in our infrastructure and built environment.

Welcome to another Wednesday post, I didn’t post on Monday because I actually got married on Sunday! Generally, Wednesday posts will be where I experiment with different topics and formats.

Follow me on Mastodon, Instagram, & Twitter for more frequent updates!

I am often a paranoid person, and so growing up in Metro Vancouver something that was always on my mind was “the Big One” (a significant earthquake) and the potential massive impacts it would have on urban infrastructure and North America as a while. This post will specifically be about Metro Vancouver, but a lot of the thoughts I share in it will be applicable to many other places.

What’s really interesting now living in eastern North America is how often people bring up the earthquake risk in the west. A friend recently moved to Seattle and told me they were surprised they didn’t “notice a difference”, which I find kind of funny: It’s not as if the ground feels spongier in places with high earthquake risk, though the Pacific Northwest (for lack of a better name) is in an unfortunate situation.

While large earthquakes do happen — for example, the Nisqually earthquake in Washington in 2001 — the smaller but noticeable quakes that you see a lot of in Japan and even California feel rather uncommon. I spent ~20 years of my life in Metro Vancouver and I cannot recall ever feeling something which I could clearly identify as an earthquake. The issue is that while the region is rather susceptible to large damaging earthquakes, the lack of smaller ones that might knock something off of a bookshelf means that earthquakes aren’t really in the public consciousness the way they are in other parts of the world. For those living in other parts of North America, I think the association with earthquakes in the west comes from school science class where you’re told “these areas get earthquakes!”, but if you actually live there, your brain pretty quickly eliminates the cognitive dissonance that is “apparently we have a big earthquake risk, but I never feel earthquakes!”

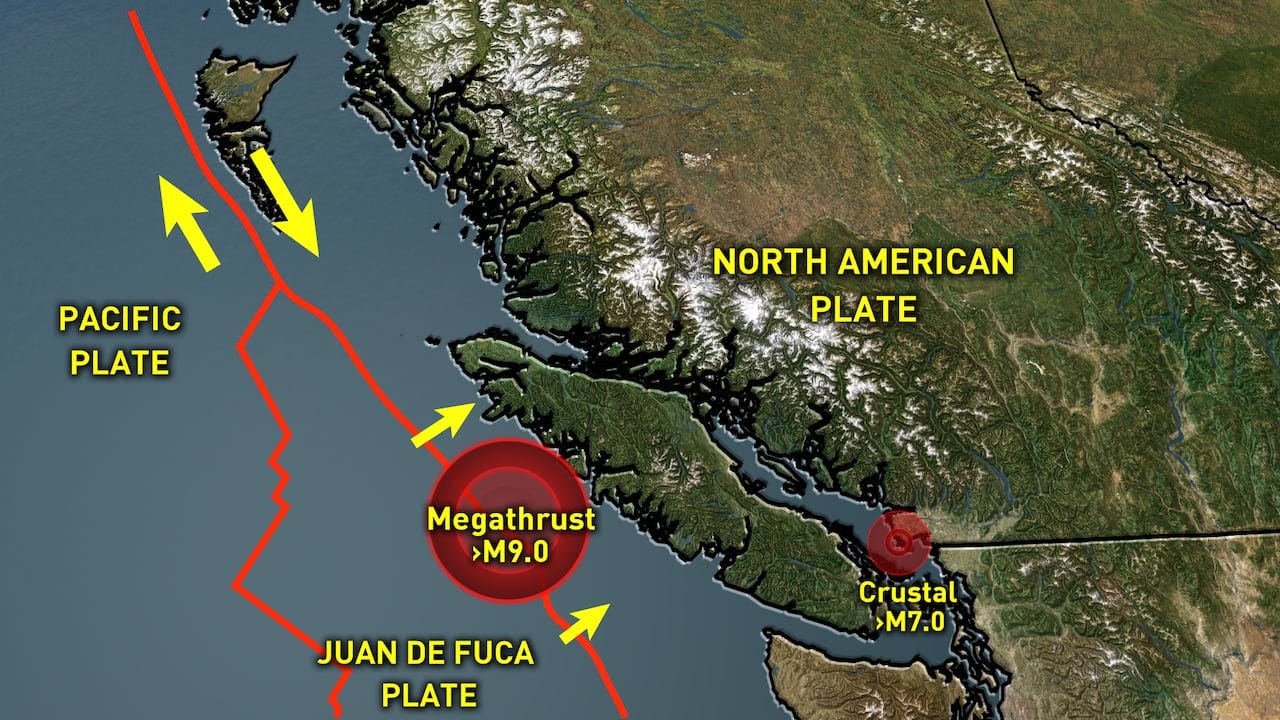

Now, talking more specifically about Metro Vancouver, the region has a number of fault lines near it, particularly to the east deep into the Fraser Valley and to the west on Vancouver Island, which can produce quakes up to around magnitude 7; there is also a major plate subduction zone off the coast (the Juan de Fuca plate is subducting the North American plate) with the potential to produce magnitude 9+ earthquakes — which would be similar in scale to the devastating 2011 earthquake off the east coast of Japan. All of this is to say Metro Vancouver and the Pacific Northwest in general is not prepared for a major earthquake, and the impacts of one would be enormous — and probably worse than even I would imagine. The purpose of this post is to discuss some of the major risks, and also the bright spots and solutions that can help get the whole region onto more solid ground (pun intended).

The Bad

If this sounds bad… it is. Metro Vancouver has a lot of serious problems it needs to tackle to better prepare itself for a major seismic event, and thats on top of climate change-driven changes needed to help protect from floods, fires, storms, and toxic air. What’s funny is that over the years Professor John Clague at Simon Fraser University has talked a lot about this and his concerns (some of which mine build off of), and yet it feels little has been done.

One major problem that is obvious is old infrastructure. This might be surprising because unlike a New York or Montreal, a lot of the major infrastructure in Metro Vancouver has been built over the last 50 or so years. While 50 years isn’t usually the entire lifespan for infrastructure, it does seem like the timescale when a lot of major work starts to be required, and there is a lot of infrastructure in, around, & over 50 years-old in the region — including the George Massey Tunnel, the Bridges to North and West Vancouver, and much of the infrastructure on the SkyTrain Expo Line. For a lot of this infrastructure, one can imagine the impacts of a serious earthquake would likely be severe — particularly the Expo Line, which is at the core of the region’s rapid transit system. A serious earthquake could take out several bridges and tunnels for long periods of time, and it could seriously impair the SkyTrain network for years as the yard near Edmonds station on the Expo Line currently supplies trains to much of the network. The Skybridge connecting to Surrey is likely also vulnerable.

Probably less appreciated than the age of infrastructure is how so much of Metro Vancouver’s infrastructure is in vulnerable locations with regards to a major earthquake (or a flood).

The most obvious infrastructure is transportation. Indeed Vancouver International Airport (the second busiest in Canada), and the Deltaport (the largest container port in Canada) are both on what are effectively islands sitting just above sea level with a high risk of liquefaction (when wet soil effectively turns to soft mud during an earthquake), as well as connections that depend on all kinds of bridges, tunnels and linear infrastructure that travels through areas which themselves are at high risk. There are also a number of major rail yards and other port facilities along the Fraser or on other low-lying lands that are at serious risk. Serious damage to even one of these major facilities in an earthquake would not only set the region back a decade or more in terms of development, but it would also make recovery efforts much more challenging.

And then there is all of the infrastructure that doesn’t get as much attention (including from me) that is just as susceptible to a major earthquake — things like electrification transmission and generation infrastructure, as well as even more niche stuff like dams and dikes. Just a few years ago, horrible damage was caused to large parts of the eastern Fraser valley from a dike damaged by flooding, and I can only imagine how much worse the potential damage could be from a major quake, not to mention the “downstream” flood impacts. The issue with so many of these “background” pieces of infrastructure is that people do not see them or interact with them all that often, and so there tends to be less public pressure to modernize and maintain when compared to visible discrete infrastructure like bridges.

Probably the most concerning element to me is not even the major infrastructure in the region, but housing stock — in particular, condo towers that house thousands of people are not designed to be very earthquake resistant. Reporting from as long as a decade ago mentions that standards for things like wall thickness used in Metro Vancouver condos align with buildings that performed poorly in the 2009 Chile earthquake, and that’s before you get to the fact that Vancouver has built towers at a very high density. Worse still, building codes are essentially designed to prevent building collapse and direct loss-of-life during an earthquake (usually not of the maximum magnitude that we know can occur!), but not repair or even medium term building survival. This means that there is a potential for a massive number of people who are without homes after a major earthquake and an extremely dangerous urban environment filled with structurally unsound towers. What’s really frustrating is that some buildings have features that are sold as making them more earthquake resistant (which to be clear is okay), but this is truly a marketing feature, not something which has been mandated — it probably should be!

And then there is the human factor. People are still not ready for a major earthquake and may not even know what to do if one happens. This will only exacerbate the impact of infrastructure and buildings, which are also not ready. When I was living in BC, lots of people I knew didn’t even have the minimum government suggested supplies for a major earthquake, and only a little over 50% of people have earthquake insurance.

What’s important to remember is that as I alluded to with buildings and earlier on with some things like the Expo Line, infrastructure does not need to completely fail to be unusable. For example, even if only a small section of SkyTrain guideway were to collapse or even become dislocated, that could shut down a large chunk of the network, and a building might be condemned even if it does not collapse. In many ways, our “engineer-so-that-things-don’t-immediately-completely-collapse” policy seems like the worst of both worlds — an additional cost burden on building things that doesn’t even guarantee they will be mostly useable after a disaster.

Of course, this is also just what gets reported on. We know that a country like Japan is very familiar with earthquakes, and a lot of people make day-to-day considerations — from the furniture they buy to where they live — based on such considerations. Engineers in that country are also deeply aware of the need to protect structures from shaking, and yet major earthquakes still take a huge toll when they happen. Given Metro Vancouver is clearly far less prepared to handle an earthquake and its aftermath than Japan and is also susceptible to major earthquakes, the potential outcome of such an event is very concerning.

The Good

While this post has probably come off as very negative, there are some things that make me happy about Metro Vancouver’s infrastructure earthquake preparedness.

For one, old infrastructure is pretty reliably being replaced — not usually for seismic reasons, but often with improved seismic performance being a listed benefit. The Patullo bridge has long been the highest risk structure in Metro Vancouver for serious damage in a disaster (even a major windstorm) and it is finally being replaced; and replacement plans for the George Massey tunnel are also moving along. In the last decade or two, we’ve also replaced or built several modern new water crossings like the new Port Mann bridge, the new Pitt River bridge, and the Golden Ears bridge. Unfortunately though, no modern link to the north shore currently exists.

While this new infrastructure is not perfect, it should perform much better than that which it replaces in a seismic event, and at the very least be easier to repair and get back into working order. It’s also worth pointing out that not everything is in horrible shape: for example, several new water tunnels have been constructed in recent years across the region, and these should be rather resistant to major earthquakes (tunnelled infrastructure often performs well).

At the same time, major public buildings are being improved at a pretty rapid pace. Buildings at UBC Vancouver in particular are being replaced at a regular clip by ones with much better seismic performance, and the same thing has been ongoing at other post secondary institutions, although as a reduced pace. Schools have also been a major focus for seismic retrofits, and as such work has been going on for a long time now, a surprisingly solid number of schools should be in passable condition after a quake — this is important because schools can serve an important role as a shelter and disaster relief hub for communities after a disaster.

We’re also doing a slightly better job with public awareness of earthquake risks, though I would chalk this up mostly to social media being a great tool for information dissemination and not significantly improved public communications. Nonetheless, it seems every year more articles come out regarding this hazard, and more products come to the local market that can help people protect themselves and their loved ones. Events like the “Shakeout” are also good for stimulating more awareness and attention. It does also seem like the government is trying (even if not quite succeeding) at elevating this issue among the public.

Probably the most exciting thing that has been developed over the last ten years or so is a rudimentary earthquake early warning system for the Lower Mainland. Such systems are well established in Japan and places like California, and sometimes even directly integrated into infrastructure (for example, automatic train stops for the Shinkansen network in affected areas), and they can provide between tens of seconds to a minute or so of warning before serious shaking begins for people to seek shelter.

Unfortunately (though this does seem to be changing a bit), the government seems to be treating the system developed by Ocean Networks Canada more like a one-off science experiment rather than the industrial strength system it should be. While its good such a system exists, and it does seem the plan is to provide a high-level of integration between it and things like transport infrastructure and emergency and medical services, I am not convinced we should be reinventing the wheel with a “made-in-Canada” solution for something that the Japanese figured out decades ago; the level of funding provide by government (around $10 million) also doesn’t scream major priority for something that could save hundreds if not thousands of lives. This is also a place where the real preparedness gaps between Canada and the US become obvious, and the US earthquake early warning system (along with lots of policy measures) simply seem much more robust — probably because the US has more and more populated earthquake prone regions than Canada.

Solutions

Now, with most of the negativity out of the way and the scene set, how can communities and governments in this part of the world better prepare?

One big thing I’d like to see more of, including from advocates, is using seismic risk mitigation as a factor to consider when planning projects and setting priorities. If you have to choose between upgrading two pieces of infrastructure, if all else is the same, I’d go for the one more likely to face problems in a quake. At the same time, improving seismic performance is a good reason to build something new: for example dispensing funding to rebuild a transit exchange or a more minor bridge. There’s also an argument to be made in investing in disaster response sites (that could store important equipment and supplies in case of a major event) and routes in and to inland cities such as those in the Okanagan as a form of stimulus and preparation.

At the same time, if I was in government, I would be pushing for structural changes. While it’s great that we will have several modern seismically-sound structures crossing the Fraser River, it seems insane that we have none crossing the Burrard inlet, where a lot of people in the region live. Maintaining basic connectivity seems like it should be a much bigger priority, as it will speed disaster recovery and rebuilding. We should also be looking to invest in infrastructure in less vulnerable locations, for example port yards and rail yards that are on high ground inland and can be used for capacity expansion, but could also act as useful fallbacks in a disaster. We should also invest significantly in the Abbotsford airport as a backup for YVR with terminal structures and infrastructure that is highly seismically resilient, and that also means doing things like providing better road access and much better transit access so that the airport can start to grow more organically. Another structural change that should be considered is the siting of critical infrastructure for things like our transit network: a number of our bus and train facilities — such as the Vancouver Transit Centre, Canada Line yard, and Hamilton Transit Centre — are in high risk areas, and long term relocation as well as the siting of future facilities needs to be better considered.

We also need to be implementing stricter building codes and how multiple buildings in dense environments might respond to a disaster. Of course, making building harder is going to run up against housing affordability concerns, and so government subsidies and studies into what changes will produce the most bang-for-the-buck are important. Little things like changing the types of light fixtures, electrical connections, and built-in furniture that is used in new development could seriously reduce the impacts of a major earthquake, at least within the home. While it’s common for homes in Japan to do small things like provide mount points for large furniture or ledges to prevent things falling off of shelves, this is still uncommon on the west coast of North America.

Home and building retrofit programs are also obviously a very good idea. We already have various retrofit programs for things like energy efficiency, and expanding that to include earthquake resilience changes like subsidized furniture fixtures, or structural reinforcement to reduce the risk of injury and property damage in an earthquake seem like a very good idea.

There should also be far, far more public education. School children should get a lot more information about earthquakes growing up, and schools can also educate families. More social media outreach and things like having government workers go door to door in high risk areas with information and resources (how to make your home safer, what to do in an emergency, and what subsidies are available) seems like a very good idea.

Earthquake early warning systems should also be supercharged — sensor networks should be expanded, research funding should increase, and performance translating into seconds of early warning time should be improved. Direct infrastructure links should be rolled out broadly, and public information systems in dense urban areas from signs to warning sirens are also worth considering.

Of course, none of this will be cheap — and you might be asking “given your advocacy around infrastructure costs, why propose things that will make infrastructure much more expensive?” The simple answer is that I don’t just want low costs, I want high value. Infrastructure that gets obliterated in an earthquake might have been cheap, but now its value is substantially reduced. Given things like rail transit lines last 100+ years, making comparatively small investments in resiliency will pay dividends in the long term.

On the whole, investments in disaster preparedness are just that — investments. Such investments can be conduits for modernizing, greening and expanding infrastructure and they can help secure the future of cities across the Pacific Northwest. They are also frankly small when considered against the costs which might be incurred in a major disaster which could certainly exceed $100 billion.

If you enjoyed this post, make sure to subscribe and feel free to leave comments on articles you’d like to see from me in the future!

Growing up in Victoria, on Vancouver Island, not far from Vancouver & on the same fault line, I felt a few earthquakes. They rattled all the dishes in the house, & the house itself shuddered for several seconds. I seem to recall they were high 4 or low 5 on the Richter Scale - but they were 40 years ago.

You should watch last night's Marketplace if you haven't. It's on Gem too and touches on some of this.