The Manhattan congestion charge will be transformational for public transit. But something is still missing.

Why congestion charges are so powerful and where the holes are in the plan.

Manhattan is getting a congestion charge in a big first for North America, and I do think it will be transformative — not just for New York, but for the continent. As is discussed in a recent CityLab article, what New York does will surely heavily influence other cities in North America, and New York is moving congestion pricing quickly (after a hilariously painful environmental review process — which is again for something that will obviously help improve the city and reduce emissions on balance).

What is it?

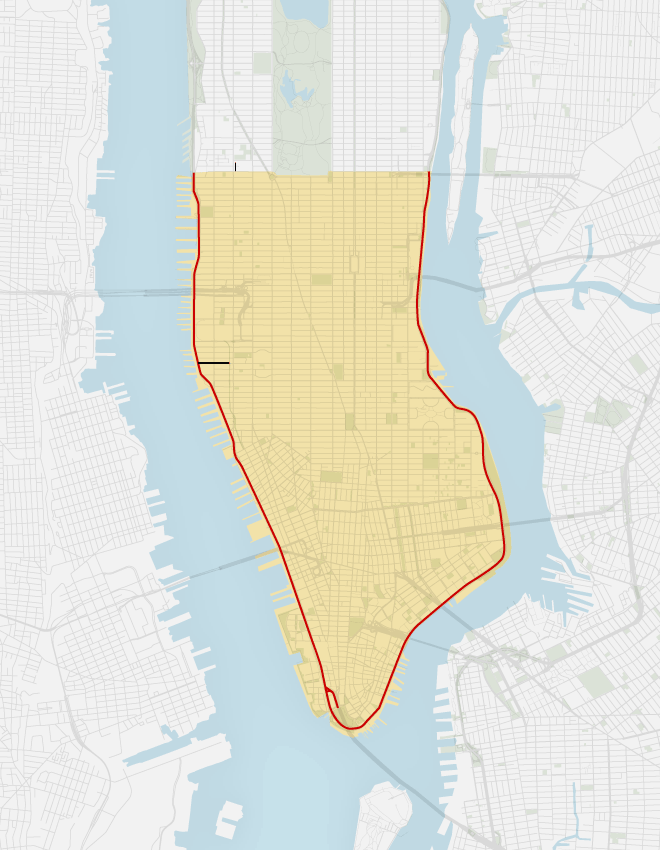

New York’s “Central Business District” tolling scheme won’t really just cover a single CBD, but will instead cover basically all of Manhattan south of Central Park (60th street, which is one block north of Central Park’s southern end), the West Side Highway, FDR Drive, and the Battery Park underpass that links the two semi-highways that encircle southern Manhattan. This is a pretty substantial area — roughly 20 square kilometres or 8 square miles — and anyone who drives into it will be paying a toll that is supposed to sit somewhere between about $10 and $20, with the zone active from 6 in the morning to 8 at night (more details can be found in this informative article from NY1).

It’s at this point in the article that I am obligated to mention that cities around the world have implemented congestion charge schemes, from London, to Stockholm, to Singapore. It’s also worth pointing out that a lot of western European cities have similar systems that are a little less legible and well known, but which have a similar goal and effect of reducing city centre driving.

Some carveouts and charge reductions will be implemented from day one, including for some low-income drivers, ambulances (duh), taxis and rideshare drivers, and potentially some commuters already being hit with tolls on their way in to Manhattan.

Now, I have my issues with MTA CEO Janno Lieber, but I will say I appreciate his desire to get congestion pricing rolled out quickly and to limit the number of additional carveouts offered. While as I just mentioned some do exist, he makes the good point that more discounts will just mean higher toll prices for everyone who does not get a carveout.

What I will say is that like we’ve seen in a city such as London, I am sure we will see tinkering around the edges with exactly how New York’s congestion charge works. For example, it wouldn’t surprise me to see the zone expand over time, see adjusted times for when it is active, or for discounts to be extended to EVs (and better yet — a gradually-reduced toll the lighter your vehicle is to encourage safer, less-damaging vehicles).

[some congestion charge in london]

The Positives

There are so so so many positives to the plans to implement a congestion charge in New York City and more broadly, and it’s moving beyond just being a plan: Cameras are already going up in various locations in preparation for a launch in early 2024.

For one, the most basic positive of any congestion charge is a disincentive to driving, which should reduce congestion in the city centre — It’s in the name! This is doubly-valuable in a city like New York, which anecdotally feels like among the most car-centric old cities out there, with huge avenues with many lanes of traffic and a dense and fairly navigable street grid. Of course, Manhattan south of 60th street is generally very dense, and that means many of the positive impacts of reduced congestion get even more of a boost.

Having less vehicles on the streets obviously means less emissions, and that’s not just CO2 but also tire and brake dust. It also means less of another type of pollution that is particularly bad in New York — noise. Noise from cars is all of the usual things, engine noise, screeching tires, rolling noise — but in New York it’s also an unbelievable amount of honking. I’d venture to guess that honking goes up exponentially with congestion, and so reducing it is likely to help with this particular nuisance a lot!

Of course, with less cars driving into the central business district, there will also be lower demand for road space, and that opens up so much opportunity for city improvement projects, and helps them pencil out by reducing traffic impacts and increasing use. I am sure a New York post-congestion charge will be a lot more conducive to rapid bus and bike lane expansion, and this will only help drive CitiBike ridership even higher!

More expensive driving will also shift the psychology for anyone who currently drives into Manhattan — and on the margins, this will reducing driving and increase transit use, walking, and cycling; it will also shift the financials for companies who send vehicles into the city for things like deliveries. I remember years ago seeing London promoting a program to encourage overnight deliveries with electric vehicles, and this seems like something we will likely see more of in New York.

There’s also the reality that for those who need to drive, or for whom options are more limited, the congestion pricing scheme will improve their life by reducing congestion! Any trade driving around with a small van will benefit a lot from this, and their saved time is part of why the price makes sense. A slight reduction in traffic numbers can have huge positive impacts, and so I basically see a congestion charges as a way for road users to avoid the status quo of a road space tragedy of the commons — and that includes transit users and cyclists!

The thing that constantly gets brought up by detractors of congestion charges — often people who want to drive into the city centre of a major city — the concerns are usually the same: “people will drive around!”, and we’ll see more congestion and emissions in suburban areas. To some extent this is true, but driving around is going to be slower (and more congested) which will make it even slower than it is now!

Perhaps the biggest element of the congestion charge plan from my perspective is that a significant part of the funding will be going to the MTA with separate allotments for Metro-North Railroad, the Long Island Rail Road, as well as the subway! But, there are problems with that…

The Problems

The Congestion Toll plan isn’t without its issues though — the one that immediately jumps out to me is that New York already has a big issue with people obstructing their license plates, scraping the letters or numbers off, and otherwise covering them in order to try and evade automated tolling and speed cameras. That’s an issue that already should be fixed, but it’s going to be an even bigger issue once the number of plates that needs to be captured increases significantly with all of the new cameras going up.

But, there is a bigger problem which is that of transit costs, as I discussed in an article earlier this year.

Transit costs in New York are already the highest in the world, so while new funding is exciting, it does feel like trying to install a new pool on a sinking ship. New York will surely benefit from the extra funding, but it would be less critical to the city if construction costs were even what they are in London — which is already very expensive to build in. At the same time, I can’t imagine the amount of funding coming from the congestion charge (as planned) is going to be getting all that much done — and then there’s always the risk that more funding just leads to further cost escalation.

More Money More Cost?

If you are anything like the many YouTube commenters and Twitter reply-people who have asked over the years, you may wonder why more funding would lead to more expensive projects.

If you’re not familiar, Parkinson’s law is a pretty broadly-applicable principle that more or less suggests that the resources needed to complete some task often will grow as large as the provided resources. More funding therefore removes a big incentive to lower prices, and makes more funding available for prices to creep higher.

It makes intuitive sense when you also consider that less-affluent places tend to pay less (and importantly, get better value) than more-affluent places. You are quite likely to get less value when you feel you have more to spend. There is just more room for overbuilding and gold-plating.

The point of this is not to somehow call the congestion charge a failure because New York hasn’t fixed its big construction cost problems — as I mentioned above, there are a ton of benefits to a congestion charge, which is why it’s such a good policy.

No doubt congestion charge is great — because it provides so many benefits in general. Even if nothing change for transit, the congestion charge would still make New York notably better!

Well said--the congestion charge is great, but better still would be reducing transit capital and operating costs!

Also want to stress before using sticks, use carrots to attract transit riders. Look at SF vs. Calgary. SF has more expensive gas and downtown parking than Calgary. SF has $7 tolls while Calgary has none. But in 2019 the CTrain got over 2x the per-mile ridership of the BART because individual CTrain lines ran every 5 minutes while individual BART lines ran every 15.

And you can't really fine people who evade tolls either, which would be the best solution to that issue as even if you place face cams, the driver can still block their face as if it were the sun